Shipman replies: Mata Hari was a sucker for a uniform, relied upon men to give her money to support her extravagance, and took no notice of what others made of her itinerary.ĭetermined to convict, French intelligence agents got Mata Hari to admit she had taken money from a German officer, and after they in turn offered her money to spy on the Germans, they accused her of being a double agent. Why did she travel so much to Germany, England, and France, always consorting with military men? The answer is simple, Ms. And Mata Hari - a so-called “international woman” - came under suspicion.

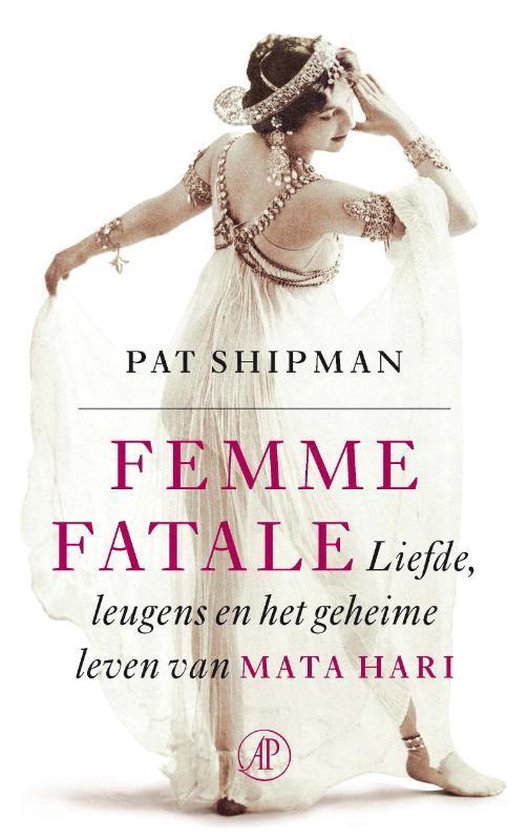

Who was to blame? Rather than accepting responsibility for the catastrophe, the French government, especially its intelligence branch, claimed that spies informing Germans of French military plans had undone the nation. Her titillations could be enjoyed as - shall we say - a cultural experience. She combined, as Pat Shipman notes in “Femme Fatale: Love, Lies, and the Unknown Life of Mata Hari” (William Morrow, 448 pages, $25.95), the sacred and profane. Her adopted name, taken from a Malay phrase, means something like “sunrise.” With the dim lighting and a pair of small, cymbal-like cups covering her mammaries, she was able to enchant European audiences for the better part of a decade, claiming to offer dances that had their origins in the sacred rites of the East. Her complexion was swarthy, and in costume resembled one of those goddesses hanging off of Indian temples. They parted in acrimony after several years together in the tropics.Īlthough Gretha had an almost matronly figure, she moved well and seems to have made a keen study of native dancers. But MacLeod turned out to be a tyrant and Gretha, as she was known then, could not suppress her flirtatious nature. Rudolf MacLeod, 20 years her senior, and a veteran of 20 years of slogging it out in vicious wars in the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia), obliged her. She adored her wayward n’er-do-well dad with the gift of gab, and she grew up looking for a handsome man in a uniform to marry. Adam Zelle treated his daughter like something special. She began as the “little Dutch girl,” Margaretha Geertruida Zelle, to borrow a phrase from Toni Bentley’s entertaining and authoritative “Sisters of Salome” (2002). French intelligence, it seems, fabricated a case, determined to find a scapegoat in an exotic courtesan who happened to be in all the wrong places at all the wrong times. Mata Hari’s recent biographers doubt the evidence against her. Greta Garbo played her on the big screen as the subversive siren redeemed by love. She is a perennial of children’s books devoted to famous spies and secret agents and no less of a draw in biographies for adults. Mata Hari, the femme fatale convicted of espionage and executed by the French during World War I, is hardly a virgin subject for biography.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)